The Abuja Treaty of June 1991 laid the foundations for the creation of the African Economic Community (AEC), in which the economies of the African Union (AU) Member States should be fully integrated by 2028 in order to develop and face globalization. It seems obvious that the objectives and provisions of the Treaty essentially tend to organise a continental integration process, thus materialising the existence of a certain African specificity.

Today, there is a plurality of views on Africa both within and outside Africa. These views bring together, based on the idea of Africa and its desire, three orders of currents based sometimes on preconceived ideas; sometimes on imaginary representations; sometimes even more concretely, on lived realities; namely, those of territories that are both scandalously rich in soil and subsoil resources and that do not always benefit the majority of exploited populations. All these three perspectives participate, in their contradictory aspects, in the “invention of Africa”. These views remind us of those of Boillot and Dembinski in their book Chindiafrique-La Chine, l’Inde et l’Afrique feront le monde demain or those of jean-Michel Sévérino and Olivier Ray in Le temps de l’Afrique. These four authors, in fact, believe that the demographic transition or the Demographic Opportunity Window that is emerging in Africa could be a very great asset for it.

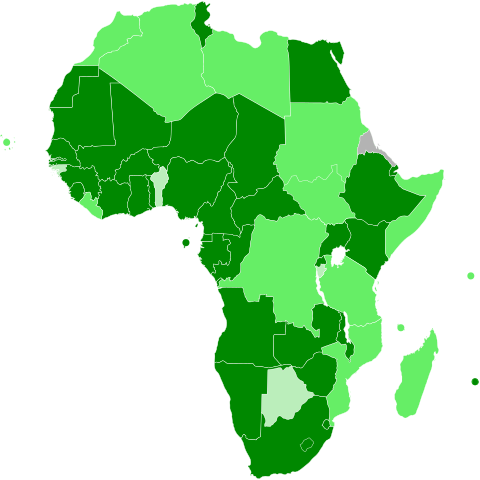

Africa is a continent marked by the diversity and heterogeneity of 54 countries, offering a contrasting picture in terms of economic development and natural resource wealth. There are four main groups of countries: those with diversified economies, oil exporters, economies in transition and pre-transition economies. In a context of boldness and continental affirmation and post-hegemonic quest for order, this dynamic contributes to the construction of another Africa that must be understood and examined in order to understand its manifestations and its contribution to Africa’s development.

Since 2000, a consensus has emerged on Africa’s potential to become the next global growth pole. Indeed, over the past ten years, particularly before the global financial crisis of 2008, Africa has experienced accelerated growth. Emergence” seems to be the objective pursued by the “policies” of many African countries. Indeed, in political speeches, it has a significant occurrence and probably appears as the focus of the execution of social projects… This seductive word is a voluptuous and enchanting powder, for François-Xavier Bellocq: “Emergence is the ability of a country to transform its growth into sustainable economic and social development“[1]. It implies a mutability of a society based on the search for individual and collective fulfilment.

It has been 14 years since the international community committed itself to achieving the Millennium Development Goals on the eve of 2015. The consequences of this unprecedented declaration are all the more discussed as the erratic evolutions of globalization seem less and less controllable. This unprecedented declaration of solidarity in favour of the poorest countries and populations is now more than ever under debate. What about the promises, the ambitious commitments solemnly proclaimed ?

I. WHAT DO WE KNOW ?

Globalization as it manifests itself today is generating more tensions and imbalances every day, too often turning into a “globalization of negative externalities”. The African economic situation is fully impacted by three characteristics of globalization: material and immaterial international exchanges that have exploded, leading to competition that is also global and partly dematerialized; the need for new rules of the game to regulate them; and finally, the transformation of our global society into an information society, with immediate and planetary means of communication and expression, which induce new modes of functioning and decision-making, including the large-scale use of intelligence (in the double sense of the term) and influence techniques.

Admittedly, Africa is indeed moving, evolving, giving itself the means to take charge of resolving its crises, to take charge of its destiny, to set out on the path of profound and lasting change. Looking back over the past four years, the 11 best performing African countries have reached the 7% growth threshold, considered a prerequisite for achieving the MDGs (Millennium Development Goals). Since 1995, growth of more than 5% has become an ordinary figure. The list of top performing countries (Ethiopia, Sierra Leone, Libya, Ghana, Rwanda, Liberia, Malawi, Zimbabwe, Nigeria, Mozambique) further highlights the central importance of commodity production and exports. The key question is whether this leap forward will remain an exceptional episode or whether it will mark a real economic take-off for Africa.

While there is no denying the real progress made in many African states, it is urgent to remain right. Growth does not necessarily mean poverty reduction and inequality. Nor is it mechanically job-creating. If the growth dynamic at work gives rise to so much hope, it is because it is based on two powerful levers: the exploitation of energy and mineral resources and the growth of domestic demand. The major risk would be that part of the continent would become bogged down in export specialisation in oil and mining resources, without breaking out of poverty. Africa’s time may not yet have fully arrived.

The risk of mass unemployment for the hundreds of millions of young Africans expected by 2050 poses a threat first and foremost to the stability of an Africa that has become more urban and subject to migration pressures reinforced by demographic pressure, and will increase the mobility of its population, which will be all the greater the younger it is.

The diaspora has certainly been recognized by the African Union as the 6th region in Africa. And the young talents of the Diaspora are returning, but unfortunately, there is no action plan accompanied by measures to achieve this, and the majority remain stuck in a pincer and end up sending, massively, a significant part – nearly 35% – of their savings to Africa to support only consumption.

In order to achieve the objective of integration, the designers of the Abuja Treaty created Regional Economic Communities (RECs), which can be defined according to three main characteristics: their geographical scope is regional; their field of integration is economic; and their institutionalization is decided by the African Union. The observation is that regional integration is still too often the result of intellectual policy speculation.

The economic emergence of Africa requires a change in the structure of its trade relations with major emerging economies and traditional partners from an economy dominated by agriculture and crafts to an industrial economy. The challenge for the continent is to diversify its economic structures and promote regional economic integration in order to create economies of scale. The challenge is also to implement coherent, coordinated and complementary strategies with regard to its various partners in order to take advantage of the opportunities offered.

II. WHAT CAN WE DO ABOUT IT ?

Full of promise and human talent, Africa remains eternally in the making. Africa is a continent currently facing two main challenges, namely the quality of growth and its sustainability. The challenge is how to ensure that Africa takes advantage of the current internal and external dynamics to create jobs for its people and reduce its dependence. This is undoubtedly one of the major challenges facing a number of African States. Each State must find its own answers according to its resources, its environment and its development dynamics.

Relations between Europe and sub-Saharan Africa are still governed by the compassionate imprint of the Cotonou Agreements, themselves heirs to the EurAfrican dream. The various regional and international agreements concluded over the past two decades have significantly changed global trade rules, influencing domestic trade policies and opening up new trade opportunities. Indeed, Africa must recover from its openness to international trade before domestic industries become competitive.

Eradicating poverty by reducing it to a socially tolerable residual level, i.e. a monetary poverty rate of less than 10%, is the leitmotiv of all national and international policies. Everything seems perfectly oiled, beautifully tied up on paper, except that we have to admit that the objectives are far from being achieved. Reversing this trend requires dynamic, proactive and visionary leadership and effective and coordinated actions to adopt and implement a coherent industrial policy.

In terms of industrialization, two main lessons can be drawn from the period of structural adjustment programmes. First, while these programmes aimed at macroeconomic stability and structural reforms that could create favourable conditions for foreign companies in particular (e. g. by protecting property rights and ensuring compliance with contracts), no coherent strategy was defined to address market failures and externalities that restricted economic activity in Africa. Second, the withdrawal of government support, even in the face of systematic market failures, and trade liberalization, which took place without taking into account the capacities of local firms, exposed African firms to foreign competition at a time when they were not ready.

III. WHAT CAN WE EXPECT ?

Hope has never been a certainty in Africa. In this case, one can only be surprised by this belief in this inexorable economic rise that could lead Africa towards emergence par excellence. The current emergence only favours populations that live and swear by the situation rents. The crucial question is whether the oil or mineral rent enjoyed by many African countries should be considered as a form of comparative advantage or as an economic lure. The “resource curse” is not inevitable, it is a political problem. It is a problem of governance deficit.

Being resource-rich, Africa can hope to achieve rapid structural change by transforming its vast natural resources and raw materials (primary products) into finished products for export, as well as by taking advantage of the lead country/follower model found in Europe or Asia and the downstream links between industrialization and the rest of the real economy. Capacity building to improve, certify and ensure the quality and standards of industrial products is important to take advantage of global market access and support the industrialization process.

The emergence raises a transcendental question to parody Kant, transcendental in that it questions the conditions of possibility of Our Common Future, to use the title of the famous 1987 Brundtland Report.

- What are the criteria defining an emerging economy and what would be the role of the African private sector? And which approach should be preferred, national or regional ?

- How can African countries revitalize the role of development finance institutions in promoting industrial finance while learning from their past failures ?

- If official development assistance was created against a backdrop of post-colonial moral debt and has continued to be used as an instrument for managing the Cold War, against a background of clientelism, how can we ensure that the Africa-Europe partnership serves their objectives, in particular the maintenance of strong economic growth and the strengthening of regional integration ?

Despite the victories of the past decade that have renewed Africa’s strategic importance and that are beginning to fundamentally and permanently reconfigure and reshape the continent’s international relations, we remain constantly on alert, ready to force reflection.

The Africa World Institute aims to become an influential platform for reflection and efficient action on good governance based on in-depth analyses and relevant diagnoses. The Africa-World couple has still not done well together. Today more than ever, the world needs Africa, just as Africa needs the world. The strategic imperative is to position the Africa World Institute as an African platform with a multi-voice boldness while evoking the need to set up a double logic of discontinuity both in the method and in the content, in particular by accelerating the agenda of the African Economic Community (ECA). To this end, we must reinvent the ethics of conviction and the ethics of responsibility to reconcile this eventful, often disunited, sometimes reconciled, but inevitably complementary couple. Independently, and while taking into account these necessary singularities, we can venture to formulate some global imperatives for the emergence of Africa:

- Accelerated economic growth, particularly through the local economy;

- An evolution and convergence of purchasing power;

- A convergence of the Human Development Index and the sharing of economic prosperity;

- A capacity to attract foreign direct investment, portfolio investment but also remittances from the Diaspora;

- A diversified economy with a high level of quantity and quality of exported products;

- Improving productive capacities, in particular by increasing the share of manufacturing value added in gross domestic product and controlling value-added chains through the agglomeration of skills;

- Improving the business environment (institutional, legal and predictable) including for the informal sector.

Jean-Baptiste Harelimana